Art from the GroundWork summer extraction residency. October 12 – December 14

Ground Up, GroundWork’s autumn exhibition is formed out of works of art made in response to the GroundWork summer residency with the underlying theme of Extraction – what is taken out of the earth. Originally, twenty artists took part (see the original outline call here). It began with a week, of intense study and field trips from 22 – 28 July, in preparation for their eventual work. Over the next weeks until October, the artists continued with their own research and making.

Ground Up: October 12 – December 14

The resulting exhibition is splitting into two, according to the themes which have been developing. Part one: Ground Up takes place October to December 2024 For the first exhibition, we chose the artists whose work most closely follows the main theme, focusing on dry land. Part two: Ground Water will show the work by artists who focused more on wet land and will show from July to September 2025 to coincide with the next phase of residencies.

Artists featured

James Aldridge, Jan-Micha Gamer, Julia Giles, Lydia Halcrow, Sarah Horlock, Lizzie Kimbley, Tamlin Lundberg, Katrin Spranger, Nicola Streeten, Sara Trillo, Liz Waugh McManus, Rachel Wright

The texts are taken largely from the artists’ own descriptions of their processes, so you can often see how they translated and incorporated experiences from the inital fieldwork into their practice.

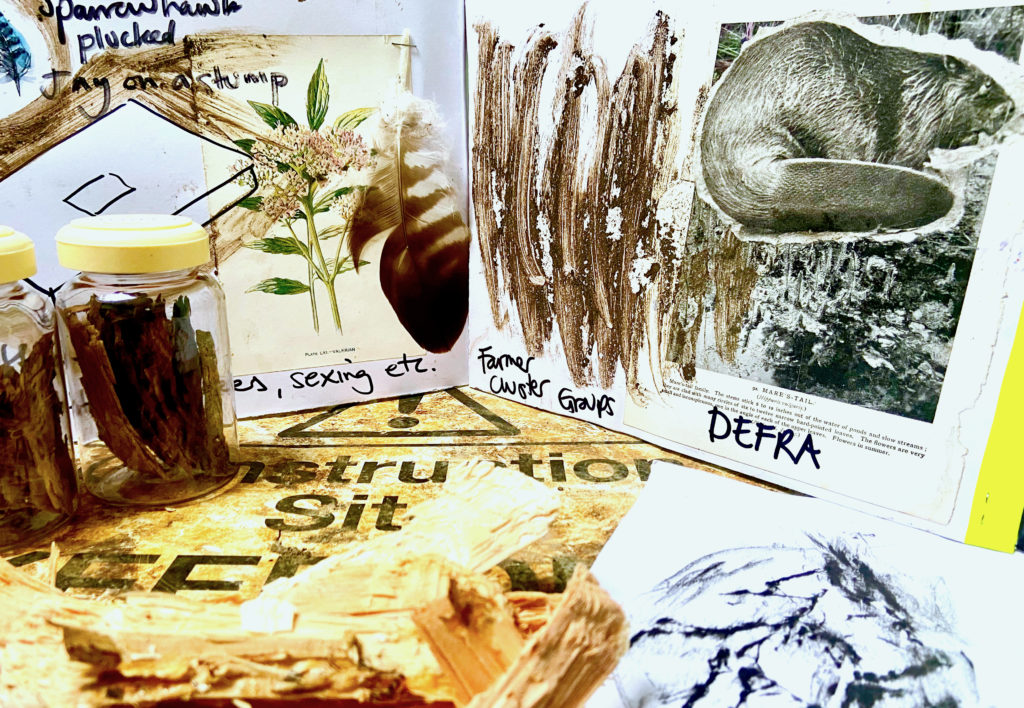

James Aldridge

The Beaver and the Whale

Mixed-media on paper with vintage maps, natural history illustrations and collected elements including beaver chewed wood, drainage pipe and mud from a beaver dam.

“Walking, talking and making with rivers forms a central part of my practice, developed though Queer River (www.queerriver.com) a research project that I set up in 2020.”

“The Beaver and the Whale documents the research I have carried out into these animals in relationship to two Kings Lynn rivers, the Gaywood and the Nar, and The Norfolk Rivers’ Trust beaver site on the River Glaven.

My research has focused on the impact of the extraction of animal bodies from wetland/marine ecosystems. Beavers hunted for fur, meat and castoreum, Bowhead Whales for blubber and baleen.

Alongside beavers and whaling, I’ve been looking at wetland birds that were hunted to extinction in the UK, for sport, taxidermy and fashion. Some of whom are now returning with the aid of a warming climate (which leaves areas further south too hot or dry), others such as Eurasion Cranes have, like the beaver, been helped by reintroduction projects.

Each of these animals plays an important role within its ecosystem, and its extraction from that system leaves it poorer and less resilient to man-made changes. Returning Beavers, Spoonbills and others are returning to a landscape impacted by development and climate breakdown, with straightened, polluted rivers, drained wetlands and increasingly extreme weather patterns.

Bowhead Whales, once numbering around 50.000 in the East Greenland-Svalbard-Barents Sea (EGSB) population, were reduced to less than a hundred by whaling and now still only number around 350 animals. Eventually whale oil gave way to fossil fuels, and now fossils fuels begin to give way to wind energy, but the legacy of fossil fuels still threatens the whales’ future though the loss of sea ice, increasing hunting by Orca and disturbance by humans.”

“My work layers the past, present and future of this area and its watery inhabitants. Maps from the 1950s are overlaid with flood levels predicted for the 2050s, as the ruins of a WW2 RAF camp on the Glaven have been overlaid with beaver dams and lodges.

I see this work as a beginning. It represents me starting to get to know this area of Norfolk in a deeper way, gathering together information through collaborating with rivers and their communities, both human and non-human.”

Jan-Micha Gamer

Salt sculptures

“My artistic practice is driven by a desire to understand and portray the multifaceted motivations and consequences inherent in material usage – from the hyper-local to the global scale; from the historic to the visionary.

My aim is to explore the multifaceted significance of salt, both within the local context of Norfolk and on a broader scale. This journey is driven by a profound encounter I had during a train journey near Eisenach, where the imposing Monte Kali, a vast salt deposit predominantly comprised of industrial waste salt from potash production, caught my attention. This experience sparked reflections on salt production’s dynamics and applications.”

The Ecology of Folly

Table salt, salt-encrusted plants, steel wire mesh, wooden sticks, cotton fabric, ceramic platter, soil

“Ranging from its role as a by-product in industries such as fertilisers, desalination plants, and salt refineries to its indispensable presence in sectors ranging from food production to ceramics, salt emerges as a pivotal yet often overlooked component of our globalised world. Central to my exploration is a desire to investigate the inherent imbalances in salt utilisation, particularly regarding the generation of salt waste and its environmental repercussions. By examining salt’s historical, ecological, social, and cultural dimensions, I aim to shed light on the complexities of this substance and inspire conversations on sustainable resource management. In Norfolk, where traces of salt’s historical significance permeate the landscape, from salt marshes to place-names, I intend to delve deeper into its evolving narrative.

Chronostasis

Fired table salt bowl

From its historic role as a prized commodity in medieval trade to its contemporary perception as a commonplace material, like road salt, I seek to unravel impacts of salt. Furthermore, I aspire to experiment sculpturally with salt as a medium, exploring its transformative properties in dialogue with water and its interactions with other materials. Through artistic innovation and expression, I aim to provoke contemplation and dialogue on the profound influence of salt on our lives and environments. In summary, my objective for the residency is to create engaging artworks that encapsulate the significance of salt while fostering a deeper understanding of its implications, both locally and globally.”

Entropy Triptych

Kiln-fired table salt, pressed plants, copper oxide, steel wire mesh

Naturae Mirantibus I

Table salt, branch, miniature glass display case

Naturae Mirantibus II

Table salt, branch, glass cloche with wooden base

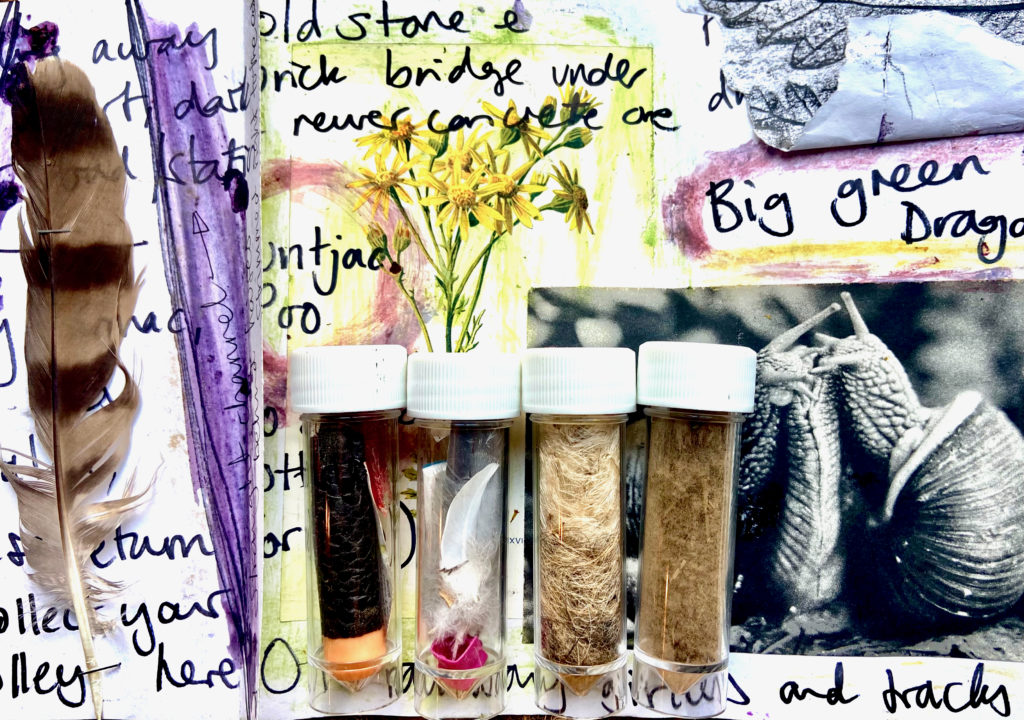

Julia Giles

“I grew up on a mixed arable farm in west Cornwall, were I now live. I trained as a painter, but now I use a range of media to explore themes related to the land. Much of my most recent work involves making compositions and wall hung sculptures with natural and man-made objects found on walks.

Like many people, I am trying to learn more and think actively about sustainability. I feel that in the western world our relationship with the land has become increasingly abusive. The climate emergency is one of the outcomes of the sustained plundering of its non-renewable resources. I’m very excited to have been part of this residency and I hope that Groundwork’s exhibitions will contribute to raising awareness of our place in the ecosystem and what we’re doing (or not doing) to protect it and live sustainably within it.

Left: Pencil drawing of fossil; Right: Horsetail

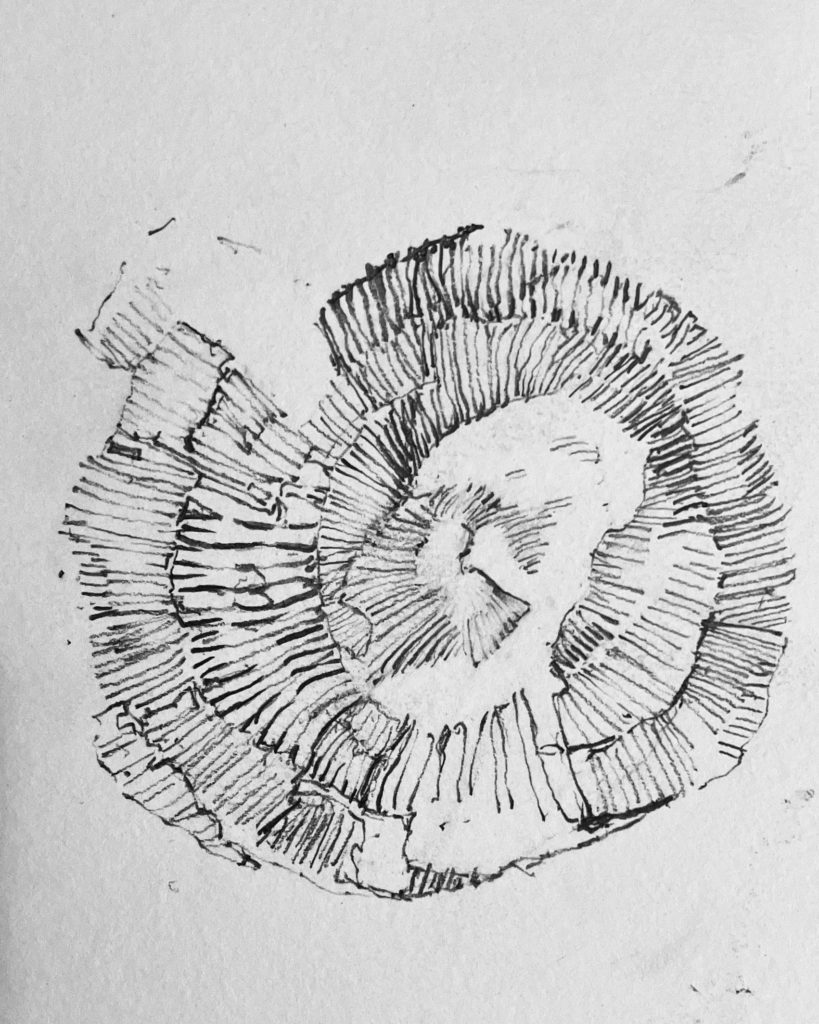

On the residency I found myself in awe of the unimaginably vast timescales in the geological history of some of the places we visited. I think this is why I was so drawn to the Horsetail plants that proliferate in the wetland at Broomhill in Reepham. Sometimes described as living fossils, Horsetails are descendants of plants that existed before the dinosaurs. Their delicate radials growing from a central stalk reminded me of spiral shaped fossils we found at the clay quarry. The antecedents of these plants were around when the fossils were living creatures.”

Fascinated by their structure and longevity, I used a spiral as motif to connect these two organisms across countless millennia. Seeing them alongside Anthropocene detritus, like that found in the soil at the quarries and at Reepham (and almost everywhere else), makes me wonder what will survive from the present into the far distant future.

Jurassic Whorl

Dried Horsetail stalks on tracing paper, A2

Segments of horsetail stalks (Reepham) arranged in a spiral. The spiral is a based on a fossil imprint found in 150-million-year-old clay (Found at the quarry, Norfolk).

Anthropocene Torso

Found objects, wire.

Wall hung sculpture in the form of a rib cage containing heart and blood vessels. Made from discarded metallic materials: Rib cage = grill rack half buried in pasture topsoil (Reepham, Norfolk), found by using metal detector. Heart = Road marker spray can (found at the quarry, Norfolk). Blood vessels = electricity cables (half buried in topsoil of a maize field, Cornwall)

Lydia Halcrow

‘For as long as the earth will endure’

Across scales and timeframes that are seemingly disparate, human and more than human encounters share common processes, and amongst them all materiality, touch, care and a sense of wonder unite them.

“The title comes from the first day history walk – from one of the wealthy family’s decree to those who were left behind and would have to pray for them ‘for as long as the earth will endure’. I’m thinking here about the dual legacy of extraction as endurance and the possibilities of restoration.

I’m working with two window structures in cast iron. Their forms connect back to the Georgian Facades built over the medieval fronts of buildings in Kings Lynn around the time the fens were drained. The long thin stepped form also connects to the flood markers – they stand at around a metre, a reminder of the likely sea level rises and the height of some of the historic flood markers on the Minster and in the Harbourmaster’s office in Wells from 2013.

In each of the 6 panels I plan to work with processes learned from the research trips here. Whilst the paper factory, the mudflat drainage (The Wash) and growth in Wells and Wild Ken Hill’s restorative farming and newly meandering river at Warham seem initially disparate, all share process allowing water to seep across the surface to then evaporate, a process that is repeated to generate different outcomes.”

Processes to make the work:

At the recycling plant, the water to breakdown the paper and clean the inks off is heated to 50 degrees, the same temperature that is the threshold between the compost mix being aerobic and a bacterial – fungal – mineral rich mix before it tips into the detrimental anaerobic. 50 degrees is also around the tipping point at which a place becomes uninhabitable for human life (or a range between 42 – 46 degrees).

The process in the paper factory of saturating and then blotting paper connects to the intertidal zone and the wetlands – a gradual letting in of water that comes in and recedes, to be repeated at intervals – again a process common with the salterns we explored with Tim Holt Wilson. The role of evaporation is common here in submerging and then allowing new forms (salt, paper, wetland bird and life forms, sands and mudflats to form)

I plan to work with 50 degree temperatures to heat water to make my own paper, to heat and melt the beeswax and to make earth inks and a molasses – wood – compost ink.

The materials I have collected at each location will be tested through these processes. The different earth pigments will be mixed with beeswax (once exported on Hanse ships from Kings Lynn we learned on Monday) and with recycled newsprint. Old felt (used to blot the recycled paper pump) will be part of a series of tests with earth inks and evaporation. The different materials will be worked into with words and fragments of maps, rubbings, textures, and pieces of rust and dead barnacles and other debris foraged from the rusting structures along the river and coast walks along stretches of the Norfolk Coast Path.

Together the work is a process based meeting of time and place that brings together the deep time of earth pigments, and the current and future time of the foraged human debris and its long future legacy – and its dual possibilities of ongoing extraction or of regeneration seen in the pair of windows as views to two possible futures.

Sarah Horlock

Artefacts created from clay, chalk and flint, and found materials collected during the residency, are displayed alongside flint knapping waste and chalk blocks from the Neolithic mines, to act as plinths for ceramic sketches and vessels, directly referencing the chalk and flint ‘altars’ and platforms upon which special objects were placed, in particular at the closing of particular shafts, at Grimes Graves.

Extraction – excavation

Ideas relating to flint forming fossils and casts of organisms, objects and surfaces lead to the exploration of ceramic slip casting of carved chalk blocks, as a means of recording and preserving ‘a moment in time’ and the physical act of extraction and excavation. Cast or created ‘artefacts’ and signifiers of the multiple layers of time and experiences that complex extraction sites, such as Grimes Graves and the Brandon gunflint mines embody, will be displayed within the vessels created from repeatedly taking casts of the chalk removal.

Landscapes of contamination

Sarah also explored the concept of ‘landscapes of contamination’, where industry or extraction has substantially altered the ecosystem and how, conversely, the flint mining in Breckland has had positive ecological impacts once nature has been allowed to recover. Through collection to relatively modern waste relating to flint knapping, Sarah has also explored how ‘craft’ creates waste and our relationship to it

To dwell on chalk

Ceramic, Grimes Graves chalk, flint, acidic solution (apple cider vinegar/lemon juice), ceramic stains & oxides.

Grimes Graves has been described as the first ‘landscape of contamination’ where the vast quantities of chalk brought to the surface altered the ecosystem of the landscape and have encouraged rare flora, associated with a sheltered chalk downland to develop, set amongst the surrounding acidic grasslands and heaths of Breckland, which is protected as a as a ‘Site of Scientific Interest’ (SSSi). Sarah used a series of chemical reactions of acid and alkali on both chalk and ceramic slip to create a series of dendritic patterns and disrupted surfaces, with a lichen-like quality. Flint knapping waste from the residency was then decorated with the common names of the rare chalk loving plants that thrive on the ground above the mines. These pieces are displayed on a mound of flint and chalk and artefacts inspired by Sarah’s creative research into the site, referencing the flint and chalk altars and platforms created within the mines

From deep time to the strike of a flint

Ceramic, Grimes Graves chalk, flint, fossils, antler.

Sarah explored ideas relating to flint forming fossils and casts of organisms, objects and surfaces and the interconnected geologies of chalk and flint. Visits to contemporary and historic quarries during the residency, and archaeological evidence for flint mining in Breckland lead to the exploration of ceramic slip casting of excavated/carved chalk blocks, as a means of recording and preserving ‘a moment in time’ and the physical act of extraction and excavation. Each cast, poured into a freshly carved cavity in the chalk, forms a small vessel which preserves the marks and process of making and extracting.

Layers of time: Cast or created ‘artefacts’ and signifiers of the multiple layers of time and experiences that complex extraction sites, such as Grimes Graves and the Brandon gunflint mines embody, will be displayed within the vessels created from repeatedly taking casts of the chalk removal. Sketches and words relating to time will be displayed within the vessels using ceramic transfers.

Deep time, familial time, seasonal time, moment in time: This is represented by slipcast vessels, each cast from a single block of chalk as it excavated and carved away. One will represent ‘deep’ time, both geological and ancestral, represented by real, cast and created fossils. Another will represent generational/familial time; the continued re-use of a site over time by a community and the passing on of skills from generation to generation. Historical evidence for the Brandon families/lineages involved in the gunflint industry and conversations with for current flint knapping families. Another vessel will represent seasonal time and episodic extraction, referencing evidence from Grimes Graves using antler picks shed by the same stag on different years in shallow pit flint workings in a linear group, suggestive of a group with a relationship with a particular stag or herd returning to the same group of pits seasonally. A final vessel will reference the experiential moment in time; the strike of an individual flint, or the fingerprint left in clay and chalk slurry on an antler pick. Moulds made from a paste from the crushed chalk from the ‘excavation’ process will be used to create slip cast flints.

Lizzie Kimbley

Rope Walks

Handmade cordage with paper, paper yarns, natural dyes and found material

Burden Rope

Handmade cordage with newspaper

Lizzie Kimbley is a textile artist based in Norwich. She works with woven textiles, natural dyes and basketry techniques to explore responsible design and connection to place. Concerned by the way we use and discard materials, and the need to value our natural resources, Lizzie works with repurposed materials as well as those that are gathered or found.

The visit to Palm Paper inspired Lizzie to consider the speed and movement of materials in industrial processes and how this contrasts with the slower rhythms of making by hand now and in the past. Hearing about the honeysuckle rope used at Seahenge inspired further research into the ropemaking history of Kings Lynn. In response to this, Lizzie has been mapping the old rope walks of Kings Lynn making cordage from repurposed and found materials as she walks.

Tamlin Lundberg

Disrupted Geologies

’Extracted hagstones, chalk and sand from Caistor Chalk Quarry, found hagstones from walks, iron concretions from Ling Common, foraged wild clays from Tas tribituraries at High Ash Farm and eroding Norfolk coastlines, commercially sourced clays.

Fluctuations in Chalk

Media: Cloth, Chalk, Graphite

‘Everything is in process’ – Tim Holt-Wilson

Noticing and valuing the subtle variations of chalks in the landscape, even the bedrock and geologies are in flux and alive.

‘Restoring land without restoring relationship is an empty exercise. It is relationship that will endure and relationship that will sustain the restored land’

Robin Wall Kimmerer ‘Braiding Sweetgrass

Building relationships to place through walking are central to my work, informing making processes. This series of experimental ceramic vessels are sculpted into local geologies including flint hag stones, iron concretions and hollows. Using wild foraged materials to disrupt the predictable results normally expected with commercially produced clays invites elements of risk and questions our relationship with consumerism and homogenised products.

Combining materials sourced from a local flint and chalk quarry, alongside wild materials, has further raised questions about extraction and the anonymity of many commercial materials. Through the act of foraging, I make connections to place, using alluvial deposits from Tas tributaries, iron rich sediments from Ling Common, a disused rewilded quarry site near Kings Lynn and materials collected from Norfolk’s naturally eroding coastline.

The quarried chalks, sands and flints are in themselves disrupted geologies, having been brought up from the ground through extraction processes, often at speed, as a product. In contrast the wild clays, sands and stones have been exposed through weathering, erosion and slower transformations. Slow making and close looking are methodologies that act as antidotes to our accelerated lifestyles.

Making relationships with place, knowing its geologies, becoming sensitive to irregularities and subtle fluctuations, develops deeper appreciation of origin and belonging. Finite resources and minerals become more than a commodity, but an environment that we are part of, not separate from.

Regular walking and foraging builds emotional bonds with place and similarly the act of making with locally sourced materials creates an archive of experience, encouraging stewardship for the land.

Katrin Spranger

Contaminated Landscapes

Materials: copper sulphate, sulphuric acid, various animal & chicken bones, varnish

During my Ground Up residency, I have focused on creating with hazardous waste materials, particularly copper sulphate and dried sulphuric acid—byproducts from the technical processes I use in my practice. I also incorporated organic materials like chicken bones.

Copper sulphate crystals and sulfuric acid are used to create an electrolyte solution, a key component in the electroforming process, where copper is deposited on organic materials to create metal-coated sculptures. In one of my large-scale projects, I electroformed an old steel frame structure, but unfortunately, this caused corrosion in the electrolyte, contaminating a 90-liter tank and rendering it unusable.

Over the years, I allowed the contaminated solution to evaporate in open containers under my benches, eventually leaving only dried-up solids. The copper sulphate had formed beautiful crystals, while the dried sulphuric acid transformed into intriguing cauliflower-like formations. However, when I released these solids from their containers, the substances oxidised rapidly and eventually broke down into unremarkable gravel like pieces.

My work often comments on environmental issues and the consumption of natural resources. I am aware that my practice, which frequently involves metals, raises environmental concerns, particularly considering the significant impact of mining copper and sulphur.

In an effort to become more sustainable, I dedicated my residency to explore how I can recreate beauty from these hazardous leftovers. Combining these materials with chicken bones serves as a metaphor—interestingly, some geologists predict that due to the explosion in chicken farming, chicken bones might become a fossil record in the future. This visualises what might be ground up from future geological layers in the Earth’s crust and what will be found from the Anthropocene when humans have vanished from the planet.

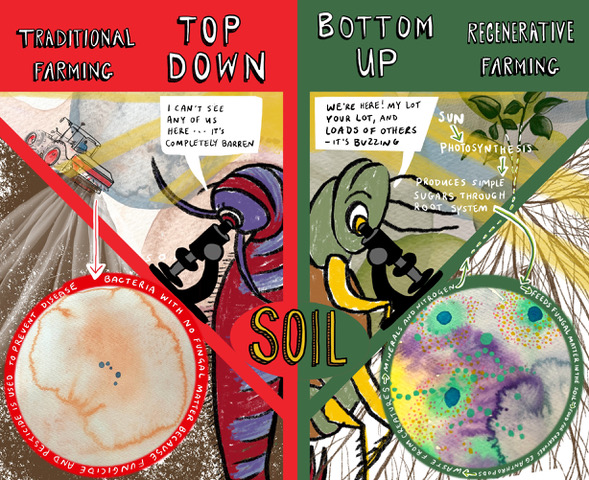

Nicola Streeten

Bottom Up

A Turkish fold comic about Bottom Up and Top Down approaches to soil inspired by the Wild Ken Hill project

A4 folded paper

published by https://colossive.com

Sara Trillo

“In recent work I have been exploring lost landscape features, and subterranean spaces, creating sculptural work inspired by what I uncover, both physically from materials excavated from these sites, and anecdotally from narratives that surface during my research. For the past two years, following an initial grant from Kent Downs AONB, I have been making work about dene holes, mysterious chalk mine shafts of uncertain age. Dene holes were dug through layers of soil to reach underground chalk strata, where chambers were carved as the chalk was extracted and raised to the surface in buckets on ropes. The chalk was then used for marling soil. Kent Underground Research Group (KURG) believe there may be as many as 10,000 dene holes in Kent alone, now largely built over, overgrown or forgotten. With KURG’s support I have descended five dene hole shafts of varying depths to view first-hand the chalk chambers at the bottom, and consider the history and ecology of these spaces, previously as locations of chalk mining, but now ecologically invaluable hibernation sites for creatures such as bats, herald moths, and cave spiders.”

Mole hole research

And here are some of Sara’s notes from Instagram recording her progress during the residency:

I have been in Norfolk @thegrangeprojects since Monday

as part 2 of my @groundworkgallery extraction residency. Having done some preliminarv research into ancient chalk mines and tunnels in Norfolk, I wanted to excavate a hole myself to try and understand the diggers who hand dug these. I decided to start by excavating molehills. It seemed an apt metaphor- the origin of the name mole is mouldywarp or mouldiwarp,

The image is a ceramic tunnel system inspired by the mole hills I excavated that I managed to connect underground by threading a piece of string through them. My ceramic tunnels may or may not contain some of the material I extracted after sieving the mole hill spoil -mostly stones, some brick and ceramic shards, some sea and snail shell, hazelnut shell. wood. and two pieces of plastic. …..Still thinking a lot about Grimes Graves and the excavations there in the 1930s.

List of works

Mole hole caps, and mole hill grills, fired black clay, all made in situ at The Grange,

Set of 13 tools

Two clay sieves, one for sifting stones, and one for sifting earth,

Pile of excavated stones/shell/shards etc from The Grange molehills,

Pile of sifted earth from The Grange molehills,

Roe deer antler used as pick to excavate The Grange molehills,

Molehill string, used to thread through tunnels, and knotted to show measurements of holes,

Map of 6 mole hills (the ones that I conjoined with string)

Map of entire molehill system

Mole gloves, textile with clay finger nails

Large hand sewn textile originally used to map holes, painted with iron ore from bacterial swamp,

Liz Waugh-McManus

During the Ground Up residency, I focused on ‘silica’, one of the most common minerals that makes up 60% of the Earth’s crust in the form of sand, flint or quartz. Made from silica, glass is one of the most useful and ubiquitous materials, in buildings, domestic vessels, scientific and optical equipment, optical fibres transporting Internet data and as an art material. Silica is a primary source of materials I use in my practice, not only in the glass cullet but in refractory moulds for casting and microchips in interactive technologies.

I responded to the local history of glassmaking. Sand has been extracted locally around King’s Lynn for hundreds of years. Mintlyn sandpits expanded from 7 employees in the 1880s to over 100 in the 1930s transporting 750000 tons of sand per year by tramway, boat or rail to glass factories all over the UK. Ships took sand to Newcastle and Sunderland and returned with coal. In 1969, British Industrial Sand, now Sibelco, was permitted to quarry 50 acres of Leziate Heath, expanding the sand industry. The ‘sand’ train still runs twice daily from Sibelco to Ardagh and Guardian Glass factories.

North Norfolk has a long history of glass, with one of the first English records of a glassmaker, a ‘vitriarius’ from continental Europe, in Bacton during King Stephen’s reign. In 1300, a French ‘verrier’ made a window for Lynn’s town hall. In the eighteenth century, King’s Lynn produced ‘flint’ lead crystal (a revolutionary innovation of George Ravenscroft assisted by Venetian expertise). Lynn Glasshouse run by Francis Jackson and John Straw produced ‘flintware’ and bottles. The twentieth century saw a glass factory established by Ronald Stennett-Wilson from the RCA, Lynn Glass, which was taken over by Wedgewood and finally, Caithness Crystal. (Stennett-Wilson also established Langham Glass in Fakenham).

Before this residency, I knew little about how glass is produced, having always used ready-melted glass cullet. Inspired by experimental archaeologists who reverse-engineered Roman and Mediaeval glass to discover glassmakers’ processes and materials. I attempted to make glass from local materials, creating batches with Leziate sand, plant ashes and chalk. I felt like an alchemist burning beechwood, bracken and samphire (glasswort) to create fluxes to lower the melting temperature of sand, distilling some to pure potash. I used chalk with sand, potash or soda ash in one experiment as lime is used to stabilise glass, but not by Forest glassmakers.

These experiments taught me that glass has always required the extraction of large amounts of natural material. Medieval glassmakers tended to move from place to place as they exhausted fuel. In the Sixteenth Century, so many trees were burnt by glassmakers for potash and fuel, that a law was passed that they should only use coal, not wood “that timber thereof is not only great and large in height and bulk, but hath also that toughnesse and heart, as it is not subject to rive or cleave, and thereby of excellent bie for shipping, as if God Almightie which had ordained this Nation to be mighty by Sea and navigation”. Ships were essential for exploration, empire, colonisation and searching for new materials. Today, soda ash is not directly extracted but chemically synthesised from common salt using the Solvay process. To reduce energy use, in the last decade, there has been a move from gas-fired furnaces to electric, some solar-powered.

Like most glass artists, I use ready-made cullet. Although creating batch from local material sounds like it should be more sustainable, the quantities of materials and energy required mean that it is better carried out on a greater scale. Archaeologists discovered that even in Roman and medieval times, there was trade in raw materials and European glassworks imported glass cullet from large producers in the Middle East. There is also evidence that glass was recycled then.

When I started using glass as a medium twenty years ago, I used waste from Caithness Crystal for cast glass sculpture. For Ground Up, I have experimented with recycling remnants of this glass, fusing it at lower temperatures to explore less energy-intensive forms. I have also cast it into a mould of Leziate sand and ‘mended’ a fragment of a glass swan.

Fused glass

A lattice in fused glass recycled from King’s Lynn’s Caithness Crystal hotshop, retaining the toolmarks of the glassmakers’ shears.

Other works on show

I have also made two pieces exploring the journeys of silica over time, from its first existence in dying stars to the Earth’s crust and from quarries to glass-making factories. I have also used glass to celebrate finds during the residency such as the samphire at Brancaster and the sea peat at Holme Beach. The latter in particular spoke to me of change over huge timescales, the peat originating in forests in a land now under the sea as coastlines change due to sea level rise, and the adaptation of nature in the piddocks making their home in the fossilised sea peat.

Glass Recipes;

Crucibles with glass

Small test samples of glass made with local sand, stone and plants.

Sand Train

Sandcast glass and audio

Three simple glass forms (cast into local foundry sand) with interactive archival audio of the sand train travelling from Leziate quarry to destinations across the UK. Highlighting recent local extraction practices.

Sea peat

Cast glass and shells

Description: Burn-out cast of sea peat

Approx 7 cm X 5cm X 4cm, display case, or tiny shelf

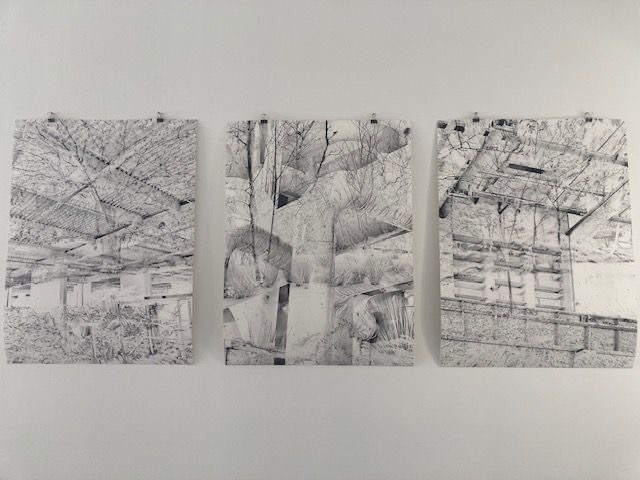

Rachel Wright

Human/nature

Digital photography on paper (triptych)

Digital images printed onto Palm Paper’s newsprint by the Newspaper Club

During the course of the residency research week I was struck by the range of human interaction/intervention with nature in the landscapes we visited. I started to think of it as a spectrum, with control at one extreme and passivity at the other, with shades of management, restoration, conservation, stewardship and care in between.

Two places we visited stood out in terms of human/nature interactions, largely because they appear so wildly different on the surface.

The Palm Paper mill on the outskirts of King’s Lynn is a very human construction – a whirl of machines, technology, heat and noise. And – the mill recycles thousands of tonnes of paper every year, repurposing waste that might otherwise end up in landfill, and meaning fewer trees need to be cut down to fuel our need for paper products.

Wild Ken Hill, on the other hand, appears at first glance to be the epitome of the natural – a beautiful, wild idyll in rural north-west Norfolk. But, of course, there is human intervention here. Nature is being encouraged to grow and thrive, tended and stewarded by people, who are carefully working to regenerate the soil and care for the land and its more-than-human inhabitants.

Both of these places challenged my perceptions of what is ‘human’ and what is ‘nature’, and made me think about our role as humans in the wider ecosystem we are part of. I take great inspiration from the writings of Native American botanist and author Robin Wall Kimmerer, who, in her book Gathering Moss, describes how “in indigenous ways of knowing, it is understood that each living being has a particular role to play. Every being is endowed with certain gifts…These gifts are also responsibilities, a way of caring for each other…This is the web of reciprocity… that which connects us all.”

Through blending images of these two seemingly polarised environments into a harmonious whole, I consider the potential of a more reciprocal relationship between humans and the natural world. Through my work I hope to challenge dominant narratives of nature/culture dualism, extractivism and hierarchy, and show the possibility of a relationship of give as well as take. A relationship that positions humans as part of their ecosystem, rather than apart from it – neither dominating controllers nor passive bystanders, but active participants in a web of reciprocity.

Highlights from the research week below

Above left to right: Sedgwick Museum Watson Collection with Liz Hide; Ivor Rowlands in King’s Lynn; Artists examining stones on Tim Holt Wilson trip to Castle Rising

Above: pics from Tim Holt Wilson trip to landscapes around Dersingham and Castle Rising

Above: pics taken by Helen Kilbride at Dersingham Bog and Leziate sands

Above: a selection of pics from Warham Camp, Ling Common and Wild Ken Hill. Photo of the pig by Helen Kilbride

Above: Nick Acheson at Holme-next-the-sea; Robert Smith CBE at Wells; John Lord’s flint knapping workshop at the Grange, Great Cressingham

The Ear of the Sea and the sea wall by Jane Scobie. Picture below by @neometa_art